- Home

- Anthony Bailey

J.M.W. Turner Page 3

J.M.W. Turner Read online

Page 3

He was small for his age, and, it would seem, something of a loner. Nevertheless he was a Covent Garden native who felt secure exploring his own part of the city. Not far away, in King Street off the north-west corner of the Piazza, was the ‘Spectacle Mecanique’. Payment of a small coin allowed you to look at the wonderful Swiss contrivances: a life-size mannikin of a boy, which appeared to write to dictation; a figure which drew landscapes; a mechanical girl who played a harpsichord; and a metal canary in a cage that hopped up and down and whistled a tune. In the market during the day mountebanks performed and, despite the by-laws, wild beasts were now and then exhibited.

One day Turner’s territory expanded: he crossed the Strand for the first time, a broad thoroughfare filled with clattering hackney coaches and private carriages. He made his way down through the tight streets and alleys to the river. In front of the tall fancy houses of the new Adelphi a stone quay had been built for barges and lighters to land and embark cargoes. But in many places the old foreshore was unimproved, with stretches of beach, rotting wharves and the remains of pilings. At low tide you could clamber down on to the shingle and strongly smelling mud and find treasures among the detritus: white clay pipes, a ship’s block, lumps of coal. Boatmen with skiffs and wherries plied for hire from the steps called ‘stairs’-Salisbury Stairs and York Buildings Stairs were the nearest. The boatmen waved and shouted to anyone who looked as if they wanted to be rowed on the river. Not far away, at Hungerford, there were wharves where you could watch coal, timber, stone and marble being landed. With the tide, lighters and barges – sails down and steered by long sweeps – shot beneath the three bridges (Westminster, Blackfriars and London). The Thames surged by, thick rippling water, with the occasional herring barrel or tree stump swirling past. Down east, he learned, was the Pool, Wapping, Greenwich, Gravesend and the sea. Up west, inland, was Lambeth, Vauxhall, Chelsea, England.

At the age of ten he went that way, west to Brentford on the Thames, to stay with his butcher uncle Joseph Marshall. The reason for the journey is obscure; it may have been ‘a fit of illness’ arising from ‘a want of air’19 – a hearsay explanation suggesting bronchitis or asthma brought on by life in a city where 900,000 people used coal fires to try to keep warm in winter. It may have been that his parents feared that their only child would follow Mary Ann into the grave unless they got him out of the gritty urban atmosphere. Or the departure for Brentford may have come about because of the domestic difficulties, springing from his mother’s ‘ungovernable temper’, that appear gradually to have shattered the Turner household. Whatever the reason, young William was taken in by the Marshalls and sent to school.

Until this moment, education doesn’t seem to have been to the fore. How much reading and writing he learnt at home is uncertain. But in Brentford in 1785 Turner went to John White’s school. This establishment had some sixty pupils – fifty boys and ten girls – and stood in Brentford High Street opposite an inn called The Three Pigeons; it was a few minutes’ walk from the market place, where the butcher and his wife lived next door to another inn, The White Horse. Also living in Brentford were Mr and Mrs James Trimmer and their expanding family. Mrs Trimmer had been Sarah Kirby, from Suffolk, daughter of a friend of the artist Thomas Gainsborough, and as well as bringing twelve children into the world she wrote books, did good works and in particular promoted Sunday schools: the Brentford Sunday school was founded in 1786 at her urging. Many of those who supported her Brentford Sunday school were dissenters, but her own son Henry Scott Trimmer was eventually ordained in the Church of England.

It may have been at the Brentford Sunday school or at John White’s academy that young William Turner first met Henry Scott Trimmer, who was a few years younger but was to become a close friend.20 It may have been in the Trimmer household, where Gainsborough was a cherished name, that Turner first realized that artists could be greatly honoured. Henry Scott Trimmer’s eldest son passed on his father’s story that Turner, on the daily plod between home and school, amused himself ‘by sportively drawing with a piece of chalk figures of cocks and hens on the walls as he went to and from that seat of learning’. The graffiti artist got more orthodox practice within White’s establishment, drawing ‘birds and flowers and trees from the schoolroom windows’.21 He was known by now as a boy who enjoyed being kept busy with pencil and paint. While at Brentford, a friend of his uncle, a distillery foreman named John Lees, asked him to colour the engravings in a copy of The Antiquities of England and Wales, by Henry Boswell. According to Lees family tradition, the foreman paid Turner twopence for each of the seventy or so plates he thus livened up.

The huge, heavy tome whose tall pages he turned was a leather-bound compendium of separately printed parts; it incorporated ‘a general history of antient castles’ and was illustrated with simple engravings of weapons, the habits of religious orders and the elements of early Norman architecture. It pictured churches, chapels, abbeys, priories and cathedrals, ruined castles and old palaces. Among the ‘antiquities’ presented with no great sophistication were Friar Bacon’s Study at Oxford, Dover Castle, Rochester Castle, Bolton Castle in Yorkshire, Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, Stonehenge, St Michael’s Mount, Holy Island and Caernarvon Castle. Nearer to home were St Paul’s Cathedral, Lambeth Palace and Syon House, the Duke of Northumberland’s mansion, just up the Thames from Brentford. Young William Turner washed in the skies with blue, the lawns and grassy slopes with green. He painted the walls of castles and churches a sandy yellow and the flags flying from towers bright red and blue. The figures of people strolling on the swards or rowing in boats were picked out: ladies’ dresses in pink or red, men’s coats in blue (or, for a change, vice versa). He carefully filled out in flat colours the leaves and branches of trees.

It was rainy-day work but it made a dent. Here, attentively studied and dramatized with colour, were all the elements and indeed the subjects, in very straightforward form, of what he was going to do in a few years’ time. Here is a crude but memorable engraving of the bizarre rock formations inside Fingal’s Cave, on the Scottish island of Staffa, and the exclamatory text: ‘Compared to this, what are the cathedrals or palaces built by man!’22

The grind at John White’s school can be imagined with some help from Captain Marryat’s young hero, Jacob Faithful, who attended a charity school in Brentford. Jacob was an unlettered orphan of Thames waterfolk, planted abruptly at the school. Despite the bullying that new boys attract and the beatings that those who seem stupid or recalcitrant are subject to, he succeeded in acquiring from the usher, the headteacher’s assistant, the rudiments of written language and then, from the dominie, a good deal of basic learning: the Greek gods, the ancient heroes; stories from the Bible and Shakespeare; the kings and queens of England. It was the right age for impressions to be made on a boy, and many of these tales and legends were, like Boswell’s castles and cathedrals, fixed in Turner’s mind. Here he would have heard of Ulysses and the Cyclops, Dido and Aeneas. Here, like Jacob Faithful, he ‘was doomed to receive an education … in reading, writing, and ciphering’.23

However, in William Turner’s case, perhaps because of his late start, perhaps because he lagged in some areas and was hyperactive in others, the effects of this instruction were not altogether successful. In syntax, in spelling, ‘must try harder’. Sometimes memories of his city life may have crowded out present moments when he should have been memorizing a times-table or declensions of a Latin verb. There were overwhelming feelings which could not be framed in words, written or spoken, but which prompted drawings. Many of his sketches ‘were taken by stealth … His school-fellows, sympathising with his taste, often did his sums for him while he pursued the bent of his compelling genius.’24 Some of his Brentford schoolmates, less sympathetic, may have laughed at the city boy for ‘talking funny’. In some verse jotted in a guidebook which he also used as a sketchbook in 1811, Turner – then aged thirty-six – seemed to be remembering this time with a gawkiness he could not

throw off:

Close to the millrace stands the school,

To urchin dreadful, on the dunce’s stool

Behold him placed behind the chair

In doleful guise twisting his yellow hair

While the grey matron tells him not to look

At passers by thro’ doorway, but his book.25

Brentford had features that may have made up for the trials of education. The village was on the river opposite Kew, with several islands called eyots which – muddy-sided and freighted with willows – like huge moored barges briefly divided the waters of the Thames. It was a historic spot, as Uncle Joseph or Mr White must have pointed out: at the ford here, of Brentford, where the twisting River Brent joined the Thames, British tribesmen under Cassivellaunus had opposed Julius Caesar’s legionaries as they marched north. Hereafter, the river was to figure powerfully in Turner’s imagination, and was to well up constantly in the poetry he attempted to write in his thirties and early forties.

By eleven he had had a city childhood and, courtesy of Brentford, a country one. Going back to Maiden Lane he may have had a sense of London, ‘the extended town’ as he later called it, with its ‘high raised smoke’, reaching out to envelop the surrounding farms, fields and commons.26 London at this point stretched from Tyburn Lane in the west, at the edge of Hyde Park, to Wapping by the river on the east. The streets and squares were spreading northwards above Oxford Street and Holborn to Marylebone, Bloomsbury and Sadler’s Wells. Islington, where many of the Marshalls lived, was still a distinct village but would not be so for long. Westminster was expanding to the south-west through Tothill Fields. South of the river, the Borough was growing towards Newington and along the Kent Road to Hatcham and Deptford. Yet Turner came back and felt at home again among the great buildings and the life that pulsed under the canopy of smoke.

It might have been good to stay at home for a while but he was soon sent off again – and once more the reasons are obscure. This time he went east, downriver. Margate was his destination, where his mother had another relative, this one a fishmonger.27 That it was his mother’s rather than his father’s family that seemed most concerned to look after him perhaps suggests that her mental health was a large factor in these evacuations from Maiden Lane.

Margate was known for its bracing air, and people were beginning to go there for sea-bathing. You could reach the resort by land or sea, but the latter was the popular way. From the Tower of London you took a hoy, a bluff-bowed sloop-rigged vessel that – weather permitting – made the trip in twelve hours. It was an exciting voyage for the first-time passenger, down the winding river past the oyster boats unloading at Billingsgate, past the ship-building yards at Deptford and the palatial seamen’s hospital at Greenwich, past the skeletons of criminals or pirates hanging in chains at Blackwall Point, past the old fort at Tilbury and then along the edge of the Blythe Sands, as the river opened up to the sea. Then along the north Kent shore – Sheerness, Sheppey – bouncing in the chop, spray flying back over the tilted deck, seasick passengers crammed in the cabin. But Turner apparently took to it, with sea-legs from the start. Margate came into view, a collection of houses set back along the beach and around the little harbour, formed by an L-shaped stone jetty or pier. Here the hoy landed amid great bustle: hotel waiters and porters touted for custom; small urchins offered to carry the bags.

In Margate, Turner – eleven going on twelve – went to Mr Coleman’s school. Thomas Coleman, a native of this Thanet part of Kent, had lived for a time in London and been converted to Methodism by John Wesley’s preaching. In Margate, Coleman established a chapel and small school and preached in the streets; he was regarded as a man ‘of great boldness and great fluency of speech’, and antagonized many of Margate’s residents. Nevertheless, he made many converts to the Wesleyan brand of evangelical Christianity; his chapel was well attended, as was the schoolroom in Love Lane.28 The effect of Mr Coleman’s ‘fluency’ and religious ardour on young Turner is indeterminable, but the boy’s knowledge of the Bible was certainly improved. Whatever Turner’s later beliefs, there is no doubt that in many respects he was a non-conformist of a taciturn kind, and the teaching of the bold dissenter may well have helped fix his burgeoning sympathies for the unorthodox.

The journey to, and the stay in, Margate also made him like the sea. Standing on the harbour jetty or playing on the north-facing beach, building sand-castles, breathing salt air, he watched the tide run in and out; he saw the sunlight striking through loose cloud the sails of ships that were making along the Thanet coast or fetching out for Ostend and Calais. He watched the waves break on the sand and the fishermen launching and hauling out their boats. And he drew. One of his first original works that survives is a drawing of a street in Margate, a downhill prospect over roofs to the masts of ships and the sea beyond. The complicated perspective of the descending street, with house fronts, rooftops and an empty cart beside a fence, is handled with remarkable skill; only the sash windows of the right-hand houses seem a bit awry, but maybe they were so in the actual houses. By the time he returned to Covent Garden again, Turner was a child not only of the city and the rural Thames but of the seaside.

The boy brought back a healthier complexion for his reimmersion in the full tide of human existence that Dr Johnson believed to be concentrated at Charing Cross. He also brought his folder of drawings to show his parents. His father had intended him to follow in the barbering trade, and William Turner senior must be congratulated for not saying, as he looked through the folder, ‘What a waste of time, young fellow! You’ll be better off helping me.’ On the contrary, William Turner gazed at his son’s work with pride and hung the drawings in the shop window and doorway, ‘ticketed at prices varying from one shilling to three’.29 Long afterwards, a few such drawings – signed ‘W. Turner’ – were cherished by customers whose perspicacity had been keen at the time, even if blended with goodwill. The hairdresser now had an answer for the common question, ‘What’s William going to be?’ He told such clients as Humphrey Tomkison and the Academician Thomas Stothard, ‘William is going to be a painter.’30

Notes

1 Redding, Fifty Years’ Recollections, i, p.198.

2 St Erasmus and Bishop Islip’s Chapels, illus. Wilton, p.9. He also signed a tombstone with his name, and inscribed his date of birth in a watercolour of Petworth Church, 1792–4.

3 Will, 2, p.29.

4 St Paul’s, Covent Garden, parish registers, Westminster Library.

5 Henry Syer Trimmer, quoted in Th. 1877, p.5.

6 Finberg, p.10; Lindsay, p.12.

7 The Survey of London, xxxvi, p.83.

8 George, London Life, p.92.

9 Ibid., p.50.

10 Hampden, ed., An Eighteenth Century Journal, p.334.

11 George, London Life, p.267.

12 Woodforde, Diary, p.105.

13 Th. 1877, p.16.

14 St Paul’s, Covent Garden, parish register, Westminster Library.

15 Previous biographers have been led astray about the date of Mary Ann’s death. After Turner’s death, when lawyers were seeking to establish whether he had living siblings, the parish clerk at St Paul’s, John Spreck, looked through the registers, missed the 8 August 1783 entry for Mary Ann and found another ‘Mary Ann Turner from St Martin in the Fields’ who was buried at St Paul’s on 20 March 1786 and has since been assumed to be JMWT’s sister. St Paul’s, Covent Garden, parish register, Westminster Library; Dossier.

16 Th. 1877, p.4.

17 Monkhouse, p.13.

18 Notes and Queries, 2nd series, cxxviii (1858), p.475; and 5th series, viii, (1877), p.114.

19 Th. 1877, p.11.

20 Henry Scott Trimmer’s son told Thornbury that Turner and his father first met in Hammersmith c. 1807 (Th. 1877, p.116), but Henry Scott Trimmer’s knowledge of Turner’s doings in Brentford seems to predate this.

21 Ibid., pp.10, 12.

22 The book was given to Brentford Library by Miss E. Lees in the

1920s and is now in Chiswick Library.

23 Marryat, pp.21–2.

24 Edward Bell, engraver, quoted in Th. 1877, pp.12–13.

25 TB CXXIII.

26 TB CII, f.4v.

27 Feret, Bygone Thanet, pp.56–7, says it was another brother. Whittingham, Geese III, p.12, says it was more likely a Marshall, uncle or cousin.

28 Bretherton, Methodism in Margate, pp.13–15.

29 Watts, p.ix.

30 Ibid., p.x.

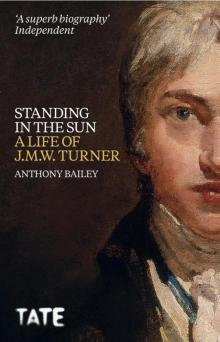

‘A Sweet Temper’: J. M. W. Turner as seen by his fellow-student Charles Turner, c. 1795

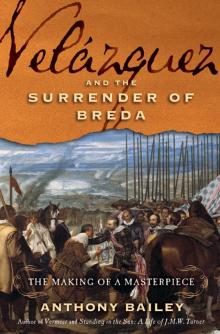

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda J.M.W. Turner

J.M.W. Turner John Constable

John Constable