- Home

- Anthony Bailey

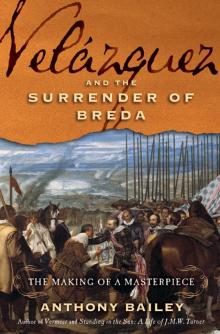

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda Read online

Again for Margot, and for our daughters, Liz, Annie, Katie, and Rachel

Stein says to Marlow:

“A man that is born falls into a dream like a man who falls into the sea. If he tries to climb out into the air as inexperienced people endeavour to do, he drowns—nicht war?… No! I tell you! The way is to the destructive element submit yourself, and with the exertions of your hands and feet in the water make the deep, deep sea keep you up. So if you ask me, how to be?…”

JOSEPH CONRAD, Lord Jim

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

I. THE TURFSHIP. BREDA. 1590

II. A BOY FROM SEVILLE. 1599–1621

III. MADRID: FOR THE FIRST TIME. 1622–

IV. WHAT HAPPENED AT BREDA. 1625

V. THE WAY TO ITALY. 1629

VI. THE GOOD RETREAT. MADRID. 1631–

VII. “BREDA FOR THE KING OF SPAIN!” MADRID. 1634–35

VIII. MADRID. 1632–39

IX. MADRID AND ARAGÓN. 1640–48

X. ROME AGAIN. 1649–50

XI. ROME: VENUS OBSERVED. 1650–51

XII. TRANSFORMATIONS. MADRID. 1651–59

XIII. MAIDS OF HONOR. MADRID. 1656

XIV. KNIGHT ERRANT. MADRID. 1658–59

XV. THE ISLE OF PHEASANTS. BISCAY AND MADRID. 1660

XVI. PENULTIMATA

XVII. LAS LANZAS. BREDA AND SEVILLE.

NOTES

A NOTE ON MONEY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PHOTOS

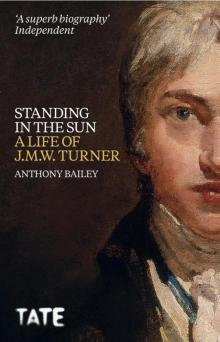

ALSO BY ANTHONY BAILEY

COPYRIGHT

ILLUSTRATIONS

BLACK AND WHITE

All by Velázquez unless otherwise noted.

The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, 1618–19, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London. The Bridgeman Art Library.

An Old Woman Cooking Eggs, 1618, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Francisco Pacheco, Portrait of an Elderly Man and Woman, c. 1610, oil on panel, Museum of Fine Arts, Seville. Junta de Andalucía.

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Adoration of the Magi, 1619, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Venerable Mother Jerónima de la Fuente, 1620, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Luis de Góngora y Argote, 1622, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Don Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke Olivares, 1624, oil on canvas, Museo de Arte, São Paulo, Brazil.

The Drinkers: Bacchus and His Companions, c. 1629, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Apollo at the Forge of Vulcan, 1630, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Joseph’s Blood-stained Coat Brought to Jacob, 1629–30, oil on canvas, Monasterio de San Lorenzo del Escorial, Patrimonio Nacional. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Infante Baltasar Carlos with a Dwarf, 1631–32, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Henry Lillie Pierce Fund. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Jacques Callot, Siege of Breda, etching from illustrated map, detail of frontispiece, 1628. Copyright The Trustees of the British Museum.

Self-Portrait, c. 1636, oil on canvas, Uffizi, Florence. Scala/Art Resource.

Christ on the Cross, 1631–32, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Infante Baltasar Carlos in the Riding School, 1636–39, oil on canvas, Private Collection, Duke of Westminster. The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Dwarf Sebastián de Morra, c. 1644, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Mars at Rest, c. 1638, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Pieter Snaeyers, The Capture of Aire-sur-le-Lys, 1641, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Portrait of a Man, perhaps José Nieto, 1635–45, oil on canvas, Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum, The Wellington Collection, Apsley House, London. English Heritage Photo Library, The Bridgeman Art Library.

A Sibyl with Tabula Rasa (Female Figure), c. 1648, oil on canvas, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas.

Philip IV, 1656–57, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Infante Felipe Próspero, 1659, oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez’s Innocent X, 1953, oil on canvas, purchased with funds from the Coffin Fine Arts Trust, Nathan Emory Coffin Collection, the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa.

COLOR ILLUSTRATIONS

All by Velázquez

Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus, c. 1618–20, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Waterseller of Seville, 1618–22, oil on canvas, Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Apsley House, London. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Villa Medici, Rome (Gardens with Grotto Loggia), 1630, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Erich Lessing/Art Resource. New York.

The Surrender of Breda, 1634–35, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Surrender of Breda (detail: Justin of Nassau and Ambrogio Spinola).

King Philip IV at Fraga (Philip IV at Fraga), 1644, oil on canvas, Frick Collection, New York.

Juan de Pareja, 1650, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Pope Innocent X, 1649–50, oil on canvas, Galleria Doria-Pamphilj, Rome. Alinari, The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Toilet of Venus (The Rokeby Venus), c. 1650, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Infanta Margarita in Pink, 1653, oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Fable of Arachne (The Spinners), c. 1656, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Mercury and Argus, c. 1659, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Las Meninas (The Family of Philip IV ), 1656, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

PREFACE

Velázquez is one of those great artists whose personal life has to be sniffed out: Suggestion and association and guesswork are all needed. His professional career as courtier and painter is fairly well documented but letters to do with how he felt and thought and lived are in very short supply. Yet he is one of the top half-dozen painters, and his paintings tell stories that allow a biographer to flesh out a portrait; the paintings—we need to remember—also sprang from his life. A good deal of information about their creator can be coaxed from them. I have written about several artists whose lives are brief in terms of surviving documentary material, and about several who come with masses of intimate correspondence in train. It isn’t easy to decide which category contains the most difficult subjects. I have always preferred to treat the biographer’s task as not only archival but reportorial, the result of experience (through feet on the ground) as well as from research (sitting in a library chair); the four senses as much as the intellect are vital tools of the trade. So, too, of course is the ability or good fortune to get at the right books and documents, and at the right people who generously allow their brains to be picked.

Among the vital documents for Ve

lázquez are the biographical accounts left by his father-in-law Francisco Pacheco and the court painter and scholar Antonio Palomino. Pacheco’s treatise Arte de la Pintura was published in Seville in 1649 and Palomino’s Parnaso Español in Madrid in 1724; translated into English, both are printed in Enriqueta Harris’s invaluable monograph, Velázquez, of 1982. Some crucial new facts about his life have been revealed in the years since by Jennifer Montagu of the Warburg Institute, London, by Peter Cherry of Trinity College, Dublin, and by Kevin Ingram of St. Louis University, Madrid. The complicated financial underpinning of his career, which may have been kept deliberately obscured, has been recently summarized by J. M. Cruz Valdovinos. My bibliography gives details of these sources and serves I hope as an acknowledgment to the many other authors who have provided grist for my Velázquez mill. Distinctions are invidious, but let me say here that the works of Julian Gallego, Jonathan Brown, John H. Elliott, and Geoffrey Parker were indispensable. For Spanish background, Cervantes’s Don Quixote remains the essential guidebook—English-speaking people who don’t get its humor and find it prolix and obscure should try the marvelous Everyman edition, which uses the 1706 English translation of P. A. Motteux, a French Huguenot who came to live in England. The traveler Richard Ford, in the first half of the nineteenth century, brought out handbooks and gazetteers that still convey the gritty essence of Spain. I have used one particular painting, one of Velázquez’s greater pictures if not his greatest, as a touchstone and frequent means of entry into his work and his world. This could threaten now and then to overbalance my effort, but I plead the example of the master, several of whose paintings have a similar dual focus, like plays within a play, with a picture of one event visible inside the scenery of another. Both artistically and politically what was happening on the smaller stage of the Low Countries had a profound impact in the larger arena of imperial Spain. Two countries geographically distant from each other were intricately involved in each other’s fortunes by way of the lifeblood of their soldiery, the cost in cash of their conflict, and—in relation to Diego Velázquez—by a work of art I am especially concerned with. I have perforce shifted the scene back and forth between them. Finally, I should make it clear that I have used a small amount of novelist’s license in the first chapter, setting the ball rolling (or the butterfly’s wing beating). But the facts on which I base my account of the turfship venture in the Netherlands are to be found in books and documents in the Breda archives.

My researches and reconnaissances were interrupted by the World Cup—the football/soccer championships—held in South Africa in 2010. In these, Spain and the Netherlands fought their way past the other countries’ teams to the finals. They had never played against each other before in such a tournament and deep memories of their often hostile sixteenth- and seventeenth-century political and military entanglements suddenly surfaced, together with occasional appreciation of their mutual debts. War with Spain assisted in the formation of the young Dutch nation. War between the United Provinces and Spain helped complete the achievements of the Dutch golden age and, depleting Spain’s fortunes, write finis to the Hispanic empire as a great power. Both countries have had long overseas histories, and both were by no means considerate colonizers, intolerance and even savagery abroad balancing their reputations for creativity and easygoing behavior at home. However, when the two national teams squared off against each other in the World Cup final, the stadium audience and television viewers worldwide were taken aback to find the allegedly now pacific and democratic Dutch playing with ruthless, unsporting aggression, while the more lately dictator-bossed Spaniards, playing stylishly if a bit quixotically, seemed unable to deliver a knockout blow. However, in overtime there came a long-deserved red card for the Dutch and an exquisite goal from the Barcelona midfielder Andres Iniesta: It was one-nil for chivalrous Spain.

My particular thanks to:

Katie Bailey for her help with reading and translating Spanish texts, Margot Bailey, Sergio Buenaventura, C. J. Fox, Dr. J. R. L. Highfield, Kevin Ingram, Martha Logan, Jack Macrae, the late Adrian Mitchell, Neil Olson, Kirsten Reach, Jon and Marianne Swan, and Lies Meijer Vonkeman.

I. THE TURFSHIP. BREDA. 1590

The wing of a butterfly beats, we are told, and a million aftereffects later, far away, a tidal wave happens. In the chain of causation that matters here, what could be taken for a starting point was not an insect wing-beat but a spade cut, as a rectangular piece of peat was sliced from soggy ground and placed onto a barrow from which it was then loaded onto a high-sided barge, heaped up, turf upon turf, in a pile that resembled an earthen shed, hollow inside, though only a few were aware of this fact. From the riverbank, where the loading was taking place, the ship’s cargo looked like a solid stack. The river was the Mark; it flowed northward through Brabant, a province in the Netherlands, to join the much larger river Waal, and thence out to the North Sea. The time was the beginning of March, 1590, a gray morning, and a war was going on. Despite this the scene near Zevenbergen seemed utterly peaceful as, the next day, the barge’s sails were hoisted and—think of a painting by the Dutch artist Jan van Goyen—the turfship set off up the Mark toward the town of Breda, past the diked green meadows in which cattle grazed.

One man, one of the only two visible crew members, stood in the bow while the skipper sat on a bench at the stern, holding the oak tiller against his hip, and listening to the rustle of water as it curved around the plump sides and the barn-door rudder and fell away astern without disturbance. There had been a heavy frost the night before and the air was damp. But during the next few hours the breeze freshened, the wetness dissipated, and the mainsail was reduced in area by being brailed up at the front bottom corner between mast and boom. Nevertheless Adriaan van Bergen, the skipper, thought it better to keep going with the flood tide under them. Every now and then a figure could be seen on the riverbanks, probably a cowherd or farmer, so far at least no soldiers from the outposts of the Spanish Army of Flanders. Before the ship came abreast of these strangers the man on the foredeck leaned down and loudly whispered, seemingly at the peat, the word “Silence!”

Not that you could hear much up on deck. The seventy or so men crouched below were indeed silent, pent up with their thoughts. They huddled together in almost total blackness, communicating by nudges and gestures, hands touching shoulders, occasionally reaching out to make sure their weapons were still there, within reach, on the barge’s hefty ribs and the bottom boards that lined the hold. The few cracks in the stacked-up peat gave just enough light and air. It was the lack of air rather than of light that most affected the party; the strong thick smell of the peat made it feel like being buried in a compost heap, and the need to swallow or—worse—sneeze and cough occasionally overcame them.

It was Adriaan van Bergen’s turfship. But its mission had been an idea floated before, by the late William of Orange, the revered if somewhat reluctant leader of the revolt against the Spanish overlords of the Netherlands. William had taken note of the fact that turf skippers could enter the walls of the occupied town of Breda most easily. Breda had been the home territory of the Orange-Nassau family. William, nicknamed the Silent because of his cautious habit of thinking a long time before acting, lips sealed, had fallen to an assassin’s gun in Delft six years before, but his son and heir, prince Maurice, had taken up the turfship idea. He had made inquiries about an experienced skipper and van Bergen, one of a family of turf handlers from Leur, was recommended. Van Bergen also had a big enough ship. The Spanish had captured Breda in 1581, killing six hundred of its citizens and plundering the place; they had occupied it ever since, and Maurice was impatient to regain it. It was not only his family seat but a key link in the ring of walled towns and forts with which Spain encircled the northern rebellious provinces. The winter still not quite over had been a tough one; it was a matter of waiting for the castle garrison or town council to order a new load of fuel, which they must do soon. Meanwhile an assault force was put together. An experienced offi

cer from Cambrai in the southern Netherlands, the mostly Spanish Netherlands, thirty-four-year-old Charles de Héraugiere, who wanted to prove his loyalty to the Orange-Nassau family, was given the command. Several meetings took place at secret locations to work out how and when the men would be embarked on the turfship. The unit was recruited by Count Philip van Hohenlohe, a relative of Maurice’s by marriage, and Maurice from his palace at The Hague organized a force of about 4,600 men of the States army to be ready to take over the city if the surprise initial attack led by de Héraugiere was successful.

At the end of February 1590 it became known that a new shipment of peat had been ordered by Breda. Maurice—who was twenty-three—set off with his small army toward Dordrecht, although, because of spies everywhere, he attempted to get it known that he was going somewhere else. Gorinchem was mentioned. The governor of Breda, an Italian named Lanciavecchia, led an opposing force of the king of Spain’s Army of Flanders toward Geertruidenberg, northeast of Breda, on the edge of the large area of river and swamp known as the Biesbos, thinking Maurice was heading there. In this time of haste and flurries of misinformation, the first attempt to embark the assault force went wrong; the blame fell on the skipper for “oversleeping” though overdrinking was more likely. The river Mark was tidal up to Breda and very low water then kept the turfship immobile for several days. But on the afternoon of Friday, March 2, the decision was made to go for it. On the following day van Bergen’s heavily laden ship sailed up the channel to the north of a small island named Reygersbosch. Here a moveable barrier or boom controlled passage to the canal surrounding Breda’s castle. Here guards waited in an outpost, and a brief inspection took place led by an Italian corporal, the guards seeing that the ship obviously carried the expected peat shipment. Then there was an uneasy period of waiting for the tide to rise high enough so that the ship could be moved in through the water gate. This was the worst time, the Dutch soldiers uneasy under their stack of peat, the leaky ship’s bilges slowly filling with water that would soon need pumping out, de Héraugiere murmuring encouraging words to keep spirits up. But just after three p.m. the tide served. The ship’s mast was lowered and the vessel was poled toward the quayside. Van Bergen now pumped away, the noise disguising some coughs coming from within the peat. At the quay a squad of Italian soldiers hauled on warps to bring the turfship in through a sort of tunnel under the walls to a sluis or lock that controlled the water level and thence into the little harbor within the castle. There the ship was moored alongside the arsenal. An impatient squad from the garrison climbed aboard to start unloading the peat.

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda J.M.W. Turner

J.M.W. Turner John Constable

John Constable