- Home

- Anthony Bailey

J.M.W. Turner Page 2

J.M.W. Turner Read online

Page 2

Turner’s age remains slightly uncertain because when he was christened in St Paul’s, Covent Garden, on that morning of 14 May 1775, the current practice in that parish was not to write a birthdate in the register. We depend on Turner himself, twenty-one years later, to affirm that the year was indeed 1775. In 1796 he exhibited a watercolour he had done of the interior of Westminster Abbey and used a floor-paving tombstone to flaunt his own name: ‘William Turner, Natus 1775’.2 In a codicil he signed on 20 August 1832 to a will made the year before, he gave the residue of his investments in Government Funds to the Royal Academy, subject to it holding a dinner for its members ‘every year on the 23rd of April (my birthday)’.3 So destiny – or the artist – chose the day which was Shakespeare’s birthday and – for complete patriotic identification – St George’s Day, the holy day of the patron saint of England.

In Inigo Jones’s great barn of a church in Covent Garden on 14 May 1775 the presumably still infant boy was held over the font and christened Joseph Mallord William Turner by the Rector, James Tattersall. However, when it came to entering the child’s three Christian names in the baptism register, the Reverend Tattersall wrote – misspelling the unusual second name – ‘Joseph Mallad William, son of William Turner by Mary his wife’.4 The future artist’s difficulties with spelling and syntax seem to have a precursor here. But no other child in the register for that year had the honour of three Christian names. Although they were names common in his mother’s family, it was as if his parents were declaring, rather than merely hoping as parents will, ‘Our child is going to be somebody.’

It was in this same 140-year-old church that William Turner, bachelor aged twenty-eight, and Mary Marshall, spinster aged thirty-four, had been married twenty-one months before. The celebrant at the ceremony on 29 August 1773 was the curate, Ezekiel Rance; their witnesses were Ellis and Martha Price. Both parties to the marriage claimed to be ‘of this parish’, and had been living in it for at least four weeks. William Turner was indeed a Devon man – which may have inspired his son to claim the same tie. William Turner’s father had been a saddler in the Devon village of South Molton, ten miles from the coastal town of Barnstaple, and William was born in South Molton on 29 June 1745. He was twenty when his father died and left him, the second son, his best white dress coat and – like his six siblings – the sum of one guinea when he reached the age of twenty-one. William’s brother John, also a saddler, achieved the locally influential position of governor of the Barnstaple workhouse; another brother, Jonathan, was a baker. William became a barber and perruquier or wig-dresser, and at some point made his way to the metropolis, where he met and wooed Mary Marshall. He was described by one who knew him as a shortish man with ‘small blue eyes, parrot nose, projecting chin, and a fresh complexion’. He ‘talked fast … [with] a peculiar transatlantic twang … and a smile was always on his countenance’.5

Six years older than her West Country lover, Mary Marshall had perhaps reached an age when she could no longer wait for a better match. There is a suggestion that, although she too came from a background of artisans and small tradesmen, the Marshalls had grander ideas of themselves than the Turners. Her father, also a William, was a ‘salesman’ of Islington, a village then just north of the city of London. One brother, Joseph Mallord William Marshall, became a butcher in Brentford, a village eight miles west of Maiden Lane. (Mallord was the surname of her maternal grandfather, an Islington butcher.) An elder sister of Mary’s married a curate, the Reverend Henry Harpur, which indicates that the family had some social ambitions.6

For the time being Covent Garden was the centre of young William’s world. The hairdresser and his wife set up home at 21 Maiden Lane, a narrow three-storey brick house in a tight little street not far from the Piazza. William Turner senior’s name first appears in the Poor Rate Collector’s Books of St Paul’s parish for the period from Lady Day (25 March) 1774 to Lady Day 1775. It appears again in the following year, 1775–6, with the rateable value, based on annual rent, of £30, and rates of £2. But then ‘William Turner’ disappears from the St Paul’s books, not to reappear for twenty years, and then in relation to 26 Maiden Lane, a property more or less opposite, on the north side of the street. However, it seems likely that unless the family moved to Devon for a while after 1776, partly validating the artist’s later claim, they went on living in the Covent Garden neighbourhood; the barber may have been a tenant or subtenant rather than leaseholder, and his landlord paid the rates. (In the rate books, some entries record ‘Paid for tenants’ without mentioning the tenants’ names.) The Turners may well have been at number 21, and then number 26, as other evidence will imply, for longer than the rate books indicate.

Covent Garden was no longer the district of high fashion it had been 140 years before. The porticoed buildings of the Piazza, designed by Inigo Jones for his patron the Earl of Bedford, were intended to attract ‘persons of great distinction’, and three earls were among the first residents. In the thirteenth century the monks of Westminster Abbey had an orchard here, the convent garden. In the seventeenth century the area was gradually developed and the fields around St Martin’s church built over. An informal market flourished for a time before the Earl of Bedford received a royal charter in 1671 to hold one. By the latter part of the eighteenth century it was ‘the greatest market in England for herbs, fruits, and flowers’.7 Carts and wagons poured in from the countryside in the small hours and unloaded at the sheds and stalls in the Piazza. By dawn light it was a boisterous scene, with the dealers crying their wares. By 7 a.m., most of the fruit and vegetables had been sold, though much litter remained.

The market had an impact on the social tone, for the neighbourhood changed. The elegant people moved west, and tradesmen, lodging-house keepers and artists moved in. Among the artists who lived in or near the Piazza were John Hoskins, the Fleming Remigius van Leemput, Samuel Cooper, Francis Clein, Sir Peter Lely, Sir Godfrey Kneller, Sir James Thornhill, his son-in-law William Hogarth, Samuel Scott and Richard Wilson. Covent Garden’s raffish reputation grew with the opening of theatres, gaming houses and low taverns evocatively called ‘night-cellars’. These caused an influx of ‘notorious characters’, so the local tradesmen said. They appealed to Westminster Sessions in 1730 about ‘frequent outcries in the night, fighting, robberies, and all sorts of debaucheries … all night long’.8 Sir John Fielding, who succeeded his novelist half-brother Henry as Bow Street magistrate in 1780, complained of all the ‘brothels and irregular houses’ in the area. Although, thanks to high corn prices, the worst of the cheap gin drinking age was past, Sir John thought enforcement of licensing laws too lax, and he condemned those, selling spirits from chandlers’ shops, ‘who are permitted to vend … this liquid fire by which men drink their hell beforehand’.9

The increasing number of dubious lodging houses and ‘bagnios’ added to Covent Garden’s notoriety. At some bagnios a customer could obtain a room and a meal and use the ‘sweating and bathing facilities’; at some he could get more. One writer in 1776 pro claimed Covent Garden ‘the great square of Venus, and its purlieus are crowded with the votaries of this goddess … The jelly-houses are now become the resort of abandoned rakes and shameless prostitutes. These and the taverns afford an ample supply of provisions for the flesh; while others abound for the consummation of the desires which are thus excited.’10

Crime, of course, was a by-product of these conditions: Exeter Street, Change Court, Eagle Court and Little Catherine Street were ‘infamous’, according to Sir John. Some alleys and rookeries off Long Acre and St Martin’s Lane were particularly dangerous for pedestrians, but James Boswell had his handkerchief picked out of his pocket while walking down the Strand, the broad former riverfront street that bounded Covent Garden to the south. In the Strand was the Spread Eagle, a hostelry much favoured by young men after the theatre, whose landlord once remarked that ‘his was a very uncommon set of customers, for what with hangings, drownings, and sudden deaths, he had a change every

six months’.11 However, towards the end of the century night-crime was reduced by the new oil-burning parish lamps, set up in all Westminster streets.

Although Turner grew up in what would now be called a red-light district, plenty of ordinary life and business went on. Many inns and chop-houses served respectable clients. The Turk’s Head, where the Reverend James Woodforde (in town from his Norfolk parish) supped and slept, stood in the Strand opposite Catherine Street, just to the west of Somerset House, and ‘was kept by one Mrs Smith, a widow, and a good motherly kind of woman’.12 Printsellers and bookdealers favoured this part of town. Tom Davies kept a bookshop at 8 Russell Street, where on 16 May 1763 Boswell first met Dr Samuel Johnson. John Raphael Smith, engraver, miniature-painter and printdealer, was in King Street. Among the district’s merchants were several jewellers and publishers. A number of perruquiers, making or refurbishing wigs, worked in Henrietta and Tavistock Streets. Apart from William Turner in Maiden Lane, a John Turner (no relation) had a hair dressing business in nearby Exeter Street. The rate books reveal the presence of several other Turners in the area.

Maiden Lane, the scene of Turner’s infancy and of part at least of his childhood and youth, was lined with mostly three-storey houses with cellars beneath. The street was formed from an old pathway through the convent garden, and in winter its narrowness made it hard for the sun to penetrate to the lower floors. When first laid out in 1631, the Lane was a cul-de-sac at its east end, but a foot passage through to Southampton Street was created in the mid-eighteenth century, and this was widened to the width of the rest of the Lane a hundred years later. Like most streets in the neighbourhood it had artistic associations. Andrew Marvell had lodged there in 1677 and Voltaire in 1727–8, the latter at the White Peruke, a lodging house kept by an old French barber and wig maker. John Ireland, watchmaker and biographer of Hogarth, lived in Maiden Lane from 1769 to 1780. Judging by rateable values it was a middling sort of street, though one Maiden Lane ratepayer was excused having to pay the rates in 1784, ‘being very poor’.

At the time of Turner’s birth, number 21 had recently been separated from the larger premises of number 20 next door. At number 20 was an auction room that had been used by the Free Society of Artists for their annual exhibitions in 1765 and 1766, and from 1769 to 1773 by the Incorporated Society of Artists for an academy of painting, drawing and modelling. Artists who attended classes here included George Romney, Francis Wheatley, Henry Walton, Ozias Humphrey, and Joseph Farington, who was to have a part in Turner’s story. In the basement beneath this room was a tavern called the Cider Cellar. Here theatregoers could drink and listen to music and singing before or after the play, while rubbing shoulders with such habitués as the silversmith J. Brasbridge, who liked going there to talk politics, and the classics don Richard Porson. Porson, the son of a Norfolk weaver, became professor of Greek at Cambridge but continued to live in London at the Temple and spend his often dishevelled nights in Covent Garden.

How much noise from the likes of Porson and company came through the party wall from the Cider Cellar, we can only guess. The Turners probably had their eating quarters in their own cellar, under the barber shop, and rooms for sleeping above. Here, or across the road at number 26, a small boy would have shuttled mostly between the two main theatres of below-stairs and ground floor: the kitchen fire and table, tended by his mother, and the barber’s chair, served by his father. To us the trade of hairdresser may seem humble enough, but to a small child it would have been fascinating: jugs of hot water brought up from the kitchen range, soapsuds and froth and steam, the swish of the straight-edged razor being stropped on leather and the gleam of the blade, the strong smell of ungents, bay rum, cologne. And then there was all the paraphernalia of hot tongs, curling papers, braiding pins and crimping irons for the dressing of wigs, and the clouds of white powder.

The wigs were splendidly various: the old perukes and periwigs, the large bushy Busbys, Club-wigs, Story wigs with their five rows of curls, and Brown Georges favoured by the King. According to Walter Thornbury,

A city gentleman or actor, about 1775, had three wigs; two being for ordinary wear, and of these one nicely powdered was brought by the barber every morning, when he came to shave the master of the family; and the third being a Sunday wig, which was taken away on the Friday and brought back on the Saturday. At spare times the barber would sit at his shop door, surrounded by his friends, while he wove flaxen curls on a dummy … The scorching of wigs was ceaseless; the clash of tongs was continuous …13

A day-to-day wig cost a guinea, but some wigs were so expensive they were worth stealing; ne’er-do-wells snatched them, even in daylight, from their wearers’ heads.

But then fashions changed. William Turner no doubt heard from his West Country relatives that, deep in the shires, gentlemen were beginning to show their own hair, though parsons, lawyers, doctors, and even actors might still be bucking the trend. Fortunately, as wigs departed, the shaving business continued to flourish. Few gentlemen then shaved themselves. Men with beards were either Jews or Turks, or possibly eccentrics like Lord Rokeby; and it was only soldiers, returning from overseas, who wore a moustache.

William Turner seems to have had a fair business. Customers came to the shop or were visited at their nearby homes and in the local hostelries in Southampton Street and the Strand. His name does not appear in the registers of the Barbers and Surgeons Guild, in which young hairdressers were apprenticed; but perhaps he served his time and acquired his skills in less formal Devon circumstances. William Turner’s thrifty nature gave rise to a story that he once pursued a customer down Maiden Lane to recover a halfpenny that he had omitted to charge for soap. One skill a successful hairdresser needed was that of keeping his customers amused, with a copy of the Daily Advertiser for those waiting and conversation that genially rattled on about the topics of the day.

When he was three and a half, young William acquired a sister. She was baptized at the parish church of St Paul’s on 6 September 1778: ‘Mary Ann, Daughter of William Turner by Mary his wife’.14 By late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century standards, William and Mary Turner were unprolific. Many families at this time had a dozen children, not all of whom would have lived. The Turners may have had other children who were stillborn or died in infancy, but no record of them has been found. We know that Mary Ann did not quite reach her fifth birthday; once again St Paul’s harboured the ceremony, which this time was tearful, with grieving parents and a perhaps bewildered eight-year-old boy. The burial is recorded on 8 August 1783: ‘Mary Ann, daughter of William Turner’.15

Mary Turner was now forty-four. The effect of her little daughter’s death must have been a great blow, even in a time when child mortality was high. Her temperament was anyway, it seems, never stable. Henry Syer Trimmer, eldest son of the Reverend Henry Scott Trimmer, Turner’s good friend, later saw an unfinished portrait Turner had done of his mother, a picture – according to young Trimmer’s reporter, Thornbury – which was

one of his first attempts … There was a strong likeness to Turner about the nose and eyes; her eyes being represented as blue, of a lighter hue than her son’s; her nose aquiline, and the nether lip having a slight fall. Her hair was well frizzed – for which she might have been indebted to her husband’s professional skill – and it was surmounted by a cap with large flappers. Her posture … was erect, and her aspect masculine, not to say fierce; and this impression of her character was confirmed by report, which proclaimed her to have been a person of ungovernable temper, and to have led her husband a sad life.16

The boy, now the sole surviving child, took refuge in his own amusements: drawing was one such, early noticed. It was recalled that ‘he first showed his talent by drawing with his finger in milk spilt on a teatray’.17 Another story concerned a professional call the barber made on Mr Humphrey Tomkison, a jeweller and silversmith who lived a few houses away along Maiden Lane. The jeweller’s son Thomas used to claim that his father was the first to

discover the boy Turner’s abilities. Thomas Tomkison told a friend in 1850: ‘On one occasion Turner [senior] brought his child with him; and while the father was dressing my father, the little boy was occupied in copying something he saw on the table.’ On being shown the drawing, Mr Tomkison refused at first to believe the boy had done it by himself. It was a precise rendering of a coat of arms engraved on a silver tray.18 From early on, young Turner seems to have had a stump of pencil or piece of chalk always in hand, and would lie on the floor or sit at a table copying pictures, engravings and advertisements in newspapers and handbills.

When he was old enough to leave the house on his own, it was to enter a world that extended further and further away from the barber shop. Down Thatch’d House Alley or Bailey’s Alley, long dark slits between the houses, to the Strand. Up Bedford Street and into the railed churchyard that led to the door of St Paul’s. Within the church, the huge white ceiling and a golden sun over the altar. Up Southampton Street or along Henrietta Street to the Piazza and the market, where, just after breakfast, the last costermongers were dragging away their laden barrows, or encouraging the donkeys that drew their carts, as they set off to the streets of customers awaiting the day’s fruit and vegetables. Empty sieves and sacks and hampers and baskets were being piled up, and streetsweepers were clearing the litter of purply-green cabbage leaves, bits of white-yellow turnip or pale-orange carrot, fragments of red apples and crushed brown chestnuts, shreds of lettuce and sprout tops and onion skins, and discarded paper jackets that had been wrapped around lemons. Maybe even an orange to be rescued from a gutter. He might drift by the caged linnets and larks being sold for a penny on either side of the east end of the church, and then wander through the flowers and flowerpots under the colonnade, where tired porters were perched on their baskets, drinking coffee from a stall. The shoeless flowergirls sat on the steps of the Covent Garden Theatre, tying up their bunches, while others clustered around the pump, chattering and elbowing one another as they watered their wilting violets.

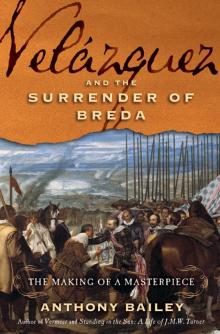

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda

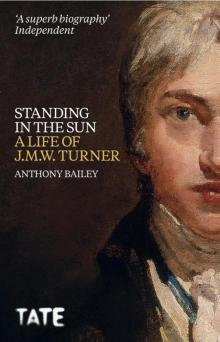

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda J.M.W. Turner

J.M.W. Turner John Constable

John Constable