- Home

- Anthony Bailey

John Constable Page 4

John Constable Read online

Page 4

Constable appears in the register of students admitted to the Royal Academy on 21 June 1800; he was twenty-four. He had passed the tests of drawing in chalk an antique figure, an anatomical figure and a skeleton, and was given a circular ivory badge, or ‘ticket’, with his name and date of admission on it. The Academy was housed in part of Somerset House, the great pile designed by William Chambers that in 1780 mostly replaced the old mansion that had stood at the eastern end of the Strand. There the Academicians fulfilled the Academy’s self-imposed obligation to train young artists without charge. Among the dozen or so who were Constable’s fellow pupils were many who never found fame, though one who remained in close touch with him to the end was Samuel Lane, a would-be portrait painter who was profoundly deaf and needed to be communicated with in sign language. (Reinagle, though not a RA student, had been exhibiting at the Academy since 1788.) Thomas Uwins, William Mulready and George Jones appear in the lists of this and adjacent years, though they were all younger than Constable. Andrew Robertson, B.R. Haydon and David Wilkie were also students during Constable’s time. The rising star at the Academy was J.M.W. Turner, only a year older than Constable but already a ten-year veteran there and, as of 1799, an Associate Academician. Constable’s apprenticeship, begun in the Antique or Plaister Academy (named after the battered plaster casts of classical pieces from which the students drew) was continued in the School of Living Models or Life Academy; in this twenty-five of the students attended in the evenings to draw a pair of models. The Keeper, Joseph Wilton, nicknamed ‘Squire’, was a nattily dressed but decrepit elderly man, no use at discipline. The RA Council had had to rule in 1792 that students were no longer to be provided with free bread for rubbing out sketching mistakes because they threw lumps of it at each other when fights broke out. Henry Fuseli, who became Keeper in 1804, on one occasion cried out during a student disturbance, ‘You are a pack of wild beasts!’ To which a student replied, ‘Yes sir, and you are our keeper.’4 In one respect Fuseli set the prevailing tone when, in a lecture, he referred disdainfully to ‘the last branch of uninteresting subjects, that kind of landscape which is entirely occupied with the tame delineation of a given spot.’5

The Visitors, who set poses for the models and supervised Life instruction, included such notable Academicians as Stothard, Northcote and Flaxman. Under them, Constable worked hard at his drawing – one later friend, C.R. Leslie, admired his Life School nudes for having ‘breadth of light and shade’, though Leslie also thought they were sometimes ‘defective in outline’. At this stage Constable was picking up hints from wherever, whomever, he could. In early 1800 he was making copies of paintings by A. Carracci and Richard Wilson; he wrote to John Dunthorne, ‘I find it necessary to fag at copying, some time yet, to acquire execution.’ Joseph Farington had lent him Wilson’s Hadrian’s Villa to copy.6 He worked again in front of Sir George’s little Claude and copied a Ruysdael which he and Reinagle had bought as a business venture for £70. But around the beginning of 1801 he was expressing to Dunthorne his disenchantment with the work of his old acquaintances (Reinagle not mentioned but undoubtedly in the frame); indeed, he was ‘disgusted … with their cold trumpery stuff. The more canvas they cover, the more they discover their ignorance and total want of feeling.’ Reinagle’s landscape of Dedham, painted in East Bergholt, was one such; Constable, who never in his life lacked feeling, described it as ‘very well pencilled’ and with ‘plenty of light without any light at all’.

Although from time to time he felt like someone from a different world, a well-to-do young man whose need to be a professional painter wasn’t clear to his contemporaries, he couldn’t complain about the access and advice he was being given. Beaumont admonished him to read Sir Joshua’s Discourses, as if offering him a route to the heart of things.7 The then President of the Academy, Benjamin West, took a painting of Flatford Mill by Constable that had been turned down for an exhibition and drew on it in chalk to demonstrate the necessity of chiaroscuro. West – himself the painter of stagy, somewhat static pictures – told him, ‘Always remember, sir, that light and shadow never stand still.’8 West realised that Constable might be disheartened by the rejection of his picture and urged him not to be. ‘Young man,’ he said, ‘we shall hear of you again. You must have loved nature very much before you could have painted this.’9 And practical support came from below as well as from on high. Another Suffolk person in town was Sam Strowger, a former ploughman. Strowger had recently served as a soldier in the Life Guards, and while doing so had like other guardsmen occasionally modelled at the Academy; he was regarded as ‘the most symmetrical’ of models and featured in many paintings including David Wilkie’s Rent Day, in which he is shown as a seated farmer with one finger raised. For Strowger, who came from a farm near East Bergholt and in 1802 became a full-time porter at the Academy with a salary of £25 a year, Constable was not an outsider. Strowger was charmed by Constable’s Suffolk views and vouched for the accuracy with which they represented all the operations of farming.10

Besides Sir George’s collection, Constable had free admission to Michael Bryan’s commercial art gallery. He told Dunthorne that he went there once a week, to look at the Orléans collection and particularly ‘some landscapes by Gaspar’ (this was Gaspar Dughet, 1615–1675, brother-in-law of Nicolas Poussin). He also went to auction rooms to look at old masters and he naturally attended the annual Academy exhibition; this afforded instruction, amusement, abhorrence and – now and then – admiration. In 1801 he told Farington that he thought highly of Turner’s Dutch Boats in a Gale and sounded proud of knowing the van de Velde it resembled.11 Nevertheless, despite this gadding about, he complained to Dunthorne that he didn’t know much about what was going on in the art world. He had moved early in 1801 to rooms of his own at 50 Rathbone Place, off Oxford Street, with one room specifically reserved as his ‘shop’ for painting, and now, contrary as ever, claimed to be a stay-at-home. He told Dunthorne that he seldom went out: ‘I paint by all the daylight we have, and that is little enough … I sometimes however see the sky, but imagine to yourself how a purl must look through a burnt glass. All the evening I employ in making drawings, and reading, & I hope to clear my rent by the former. If I can I shall be very happy.’

Once in a while his longing for home welled up. He told Farington of this and Dunthorne heard a similar cri de coeur in the winter of 1800. ‘I hope to see you in the spring, when the cuckoos have picked up all the dirt. Every fine day makes me long for a walk on the commons … This fine weather almost makes me melancholy; it recalls so forcibly every scene we have visited and drawn together. I even love every stile and stump, and every lane in the village, so deep rooted are early impressions.’ Clearly he visualised his experiences as ‘scenes’, and many of his later pictures were of scenes he must have first encountered with Dunthorne. Dunthorne, although still in place, shared Constable’s sense of loss. In March 1802 the village handyman had just finished making a cello but wasn’t feeling well, and complained to Constable that he missed him: ‘I have no comfortable companion for any serious or instructive conversation.’ Constable had just seen his mother who was visiting London; he wrote to Dunthorne, ‘I never hear of an arrival from E. Bergholt but I forthwith take my hat & stick and trudge off for the news.’ Mrs Constable had given him ‘a good account of most of my neighbours’, but Constable was told that Dunthorne didn’t look well. He put this down to the ‘unwholesomeness’ of Dunthorne’s business – presumably working with lead pipes and lead-based paint – but he hoped spring would bring his old friend a new lease of life.

The Academy year already imposed its constraints. ‘As the season advances it becomes more difficult to leave London,’ Constable reported. There were numerous picture sales and ‘much is to be seen in the Art’. However, summer arrived with the end of the Academy exhibition, Suffolk awaited, and he went to Helmingham Park beyond Ipswich to draw the old oaks. Helmingham Hall belonged to the Earl of Dysart, a member of the Tollemache family w

hich had originally lived at Bentley near East Bergholt. The connection with the Tollemaches was a lasting and fruitful one for Constable; looking ahead a little, work copying family portraits was to come his way, as were commissions for house portraits from Tollemache relatives; moreover, the Earl of Dysart bought a landscape from Constable in 1810 – his first exhibition sale. After the Earl’s death in 1821 his sister Lady Louisa Manners became Countess of Dysart and inherited Ham House, another family property near Richmond, Surrey. She eventually took on Constable’s hard-to-employ brother Golding as warden of her ill-managed Bentley woods; gifts of venison from a thankful Lady Dysart were a by-product.

In Helmingham Park Constable was on his own, sleeping at the parsonage, eating at the farmhouse and ‘left at liberty to wander where I please during the day’. The solitude was inspiring. The drawings he made he thought ‘may be usefull’. He used black chalk as for Life class nudes though his models here were trees and his influence was Gainsborough. Art out of doors wasn’t too far removed from farming, using your hands, breathing open air, and while you did so dreaming in an attached, concentrated way. Some of the drawings of trees he did at Helmingham began to show talent, an ability to see the skeletons within the forms, visualising the negatives that could be used to create positive images. Then it was back to East Bergholt. Back to the family and his ally John Dunthorne. And this year there was a new face nearby – that of a twelve-year-old girl, Maria Bicknell, the rector’s granddaughter. We don’t know where Constable first saw her, perhaps in the village street, running through the fields between the gardens of East Bergholt House and the rectory, or maybe in church, with Maria fidgeting up front and Constable in the family pew perusing a newly acquired Book of Common Prayer. During the 1800 Christmas holidays Maria may have been among the assembled Rhudde relatives. Constable was twenty-four and Maria half his age, a lot younger than Lucy Hurlock or any of the other girls who had taken his fancy. He may not have recognised the spark that flashed – he might even have been horrified by any flicker of erotic impulse – but something happened; it is visible in the painting he made of young Maria apparently about this time. The daughter of Charles Bicknell, an important London lawyer (he was solicitor to the Admiralty) who had married Dr Rhudde’s daughter Maria Elizabeth as his second wife, Maria at that age could also have had no conscious sense of what was to come. And yet between painter and sitter a current passed. He saw that small pale face with big dark eyes framed by a bonnet, a single tight curl of hair on one side of her forehead, her left hand on her hip. She looked at him so thoughtfully but impatiently – perhaps wishing he’d hurry up and finish painting her so that she could run outside and play.

A girl in a bonnet, believed to be the young Maria Bicknell, c.1800

When he was back in London in Rathbone Place Constable seemed to have a stronger sense of his own direction. Reinagle had exchanged the Ruysdael they had bought together for some other pictures and promised to pay Constable his share when they’d been sold; but Constable refused an invitation to dine with his former business partner whose work he thought mechanical.12 He told Dunthorne that it ‘would be reviving an intimacy which I am determined never shall exist again, if I have any self command. I know the man and I know him to be no inward man.’ Even so, predicting Constable’s future from the work he was involved in at this time would have been difficult. At the end of 1800 he had finished four watercolours of Dedham Vale, a sort of small-scale local panorama for Lucy Hurlock on her marriage. He was doing a lot of drawing, and was pleased when J.T. Smith offered to take some of his work and try and sell it in his shop. Yet March found him melancholy, according to Farington, and he seems to have needed as much family support as he could get: he spent a lot of time with the Whalleys in the spring and summer of 1801. Golding Constable still wasn’t convinced of John’s vocation; he thought his son was ‘pursuing a shadow’, Farington reported, and wished to see him ‘employed’. Constable might have countered that he had been employed, for instance in painting Old Hall, the manor house just across from East Bergholt church. Farington, although seeing a lot of Sir George Beaumont’s influence in the somewhat ghostly picture of the mansion and surrounding parkland, had pleased him by saying he should ask not five but ten guineas for it.13 During the summer and autumn he spent what for him was an exceptional amount of time away from both Bergholt and London. It was almost as if he were trying to test to the limit his own commitment to his roots.

Daniel Whalley, his sister Martha’s father-in-law, had a house in Derbyshire. From there, accompanied by Martha’s brother-in-law, also named Daniel, Constable went on a three-week sketching tour of the Peak District, averaging a couple of pencil and sepia drawings a day. In Dovedale, which Constable sketched as a narrow cleft running into a steep hillside, they bumped into Farington, a veteran in the picturesque, on a very hot day. Constable’s drawings were improving, though still a bit wispy, and he found his morale improved too. Possibly he felt more in touch with nature than he might have expected this far from the Stour valley; the local Derbyshire quarries provided millstone grit, the material which provided the stones that turned in the watermills and windmills of England and ground the Constables’ flour.14 He wrote to Dunthorne after this trip: ‘My visit to the Whalleys has done me a world of good – the regularity and good example in all things which I had the opportunity of seeing practiced (not talked of only) during my stay with that dear family, will I trust be of service to me as long as I live. I find my mind much more decided and firm …’

Back in London he attended a series of lectures given by the anatomist Joshua Brookes (RA students were admitted free) and he let the lectures prompt him to thoughts of ‘the Divine Architect’. He told Dunthorne – adopting a somewhat superior tone – ‘a knowledge of the things created does not always lead to a veneration of the Creator. Many of the young men in this theatre are reprobates.’ Constable gave no hint of any such thinking or any untoward behaviour. On the contrary, he was buckling down to all sorts of work. He got paid for painting the background of a picture of an ox that Mary Linwood, a celebrated embroiderer, was copying in needlework. Dunthorne was pleased to hear that he was also ‘doing something in the Portrait way’ and passed on the cheering news that Constable’s father was speaking of his son’s recent efforts in ‘quite a different way’. And then a painting called The Edge of a Wood was accepted for the 1802 Academy exhibition: it showed a thick stand of trees in which one could just make out a man sketching and a donkey and its foal peeking out from the gloomy underbrush; above, only a tiny patch of sky. Nice, but Gainsborough had been here before. And it was a pity that landscape was still on a low level in the hierarchy of art, inferior to history painting and even portraiture; landscape – so such pundits as Jonathan Richardson believed – didn’t greatly improve the mind or excite noble sentiments. At this time Dr Fisher proferred a professional post: a new drawing master was needed for the Royal Military College at Marlow. Tempted, Constable went for an interview and stayed with the Fishers at Windsor. Several fine drawings of Windsor Castle showed what he could now do. But though he was offered the job, he took soundings and several influential people advised against acceptance. Farington was one such, and Benjamin West said that if Constable accepted the post he would have to give up all hope of future distinction.15

Into May 1802 Constable spent several weeks thinking about what was the surest way to excellence as an artist. Sir George Beaumont’s collection once again proved a vital resource in decision-making. After a visit to Hagar and the Angel, Constable wrote to Dunthorne, the one person he could really unburden himself to:

I am returned with a deep conviction of the truth of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s observation that ‘there is no easy way of becoming a good painter’. It can only be obtained by long contemplation and incessant labour in the executive part.

And however one’s mind may be elevated, and kept up to what is excellent, by the works of the Great Masters – still Nature is the fountain’s

head, the source from whence all originally must spring – and should an artist continue his practice without refering [sic] to nature he must soon form a manner, & be reduced to the same deplorable situation as the French painter mentioned by Sir J. Reynolds, who told him that he had long ceased to look at nature for she only put him out.

For these two years past I have been running after pictures and seeking the truth at second hand …

He was determined instead to concentrate on first-hand truth. He was going to make no more ‘idle visits’ this summer or give up time to ‘common place people’. Farington backed him up in one aspect of this: he told Constable he should study nature and pay less attention to particular works of art.16 Constable wrote to Dunthorne that he was soon coming back to Bergholt to make ‘laborious studies from nature’. Although he was conscious of the benefits he had got from exhibiting at it, the Academy exhibition had showed him little or nothing worth looking up to. ‘There is room enough for a natural painture. The great vice of the day is bravura, an attempt at something beyond the truth … Fashion always had, & will have its day – but Truth (in all things) only will last and can have just claims on posterity.’

Constable wrote to his most appreciative listener with a young man’s dogmatic idealism, and he may not have suspected how uncomfortable things might get for him, with these colours nailed to the mast. He also wrote with difficulty, having pains in his teeth and lower jaw that caused one cheek to swell. Among his laborious studies from nature made that summer was a painting, Dedham Vale, a prospect of the Stour valley apparently from Gun Hill, near Langham. We look past a clump of trees beneath which a countryman sits with legs outstretched. Farington, seeing one of these studies, thought it ‘rather too cold’.17 Turner used the term ‘elevated pastoral’ for many prints in his Liber Studiorum but Dedham Vale is a pastoral landscape not so much elevated as cultivated – a glimpse of an English Arcadia.

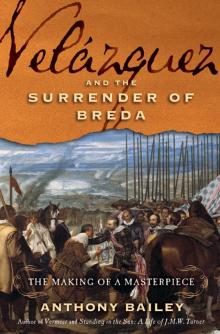

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda

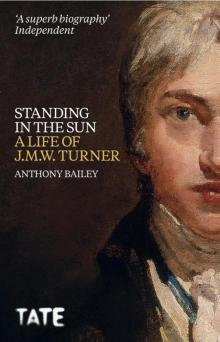

Velázquez and the Surrender of Breda J.M.W. Turner

J.M.W. Turner John Constable

John Constable